Nathan Chandrasekaran, Co-Founder/Partner at Columbia River Partners, gave this presentation at Finance Alliance’s FP&A Summit.

Columbia River Partners is a small investment firm. We’ve been around for about three years. Prior to that, I was at a larger private equity (PE) firm in New York for about 15 years.

- Capitalizing on the foundation of tech

- What are private equity firms?

- Financial reporting for many different constituents

- Sharing a financial reporting calendar with the CFO

- Key considerations for private equity firms

- Navigating the nuances of lender reporting and compliance

- Financial reporting challenges and best practices

Capitalizing on the foundation of tech

We invest primarily in the “picks and shovels” of technology. So if it's sexy, SaaS, growth equity, burning cash, we kind of run away from that. We focus on businesses that actually generate cash, have earnings, and a lower margin.

If you look at our portfolio of companies, we have a business that manufactures fiber optic cables, we have a business that distributes Chromebooks, and a business that provides IT services for K through 12.

That's where we spend our time, so we're definitely not following the trend of super SaaS and going into a big billion-dollar company. Instead, it’s, “Hey it's a good business.”

Our thesis has always been that yes, everyone wants software and everyone loves software, but you still need someone to help sell it, implement it, maintain it, and run hardware on it.

My wife works at Amazon, and she always reminds me that the most valuable company in the world is actually a hardware business. It's called Apple. But they build software. They control their ecosystem with their hardware plus the software on top of it. It’s an interesting dynamic.

Another one of our investors is a senior guy at Amazon, and they love CapEx-intensive businesses like data centers and warehouses because it makes it very hard for people to compete. It’s an interesting philosophy that they have.

What are private equity firms?

Now, let's talk about what private equity firms are.

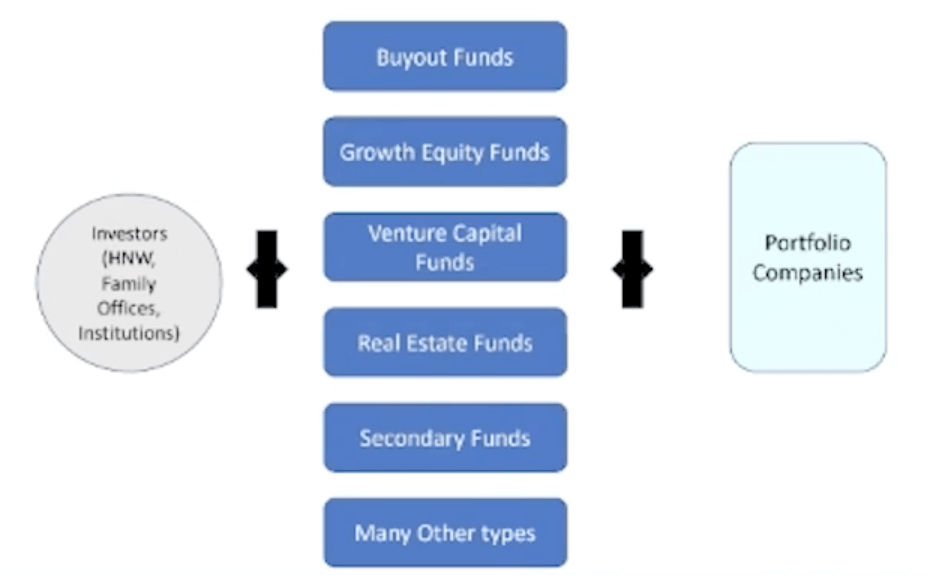

There are lots of variations of investment firms. There are buyout funds, growth equity funds, venture capital funds, real estate funds, secondary funds, I can go on. There are dozens and dozens of funds out there.

What they typically do is raise capital from high net worth and family offices and institutions, take it, and then invest it in portfolio companies, like what we do. We sit at the top; we’re the buyout fund.

Financial reporting for many different constituents

When we think about financial reporting, PE firms have a lot of constituents to deal with.

We just did a deal with a company, and I was walking them through all their different constituents. Well, we've got the management team itself, what they're looking for, their KPIs, what their burn rate is, or what their cash flow generation is.

Then, as the PE firm, we have to report to all these other constituents. There are existing investors. PE firms are always fundraising; it’s never-ending fundraising. We’re talking to potential investors, and the financials you show to an existing versus a potential investor can be different. And then we could talk about that for other reasons.

You have regulatory agencies, and you have auditors at the PE level. There are firms like Cambridge Advisors. They call them fund gatekeepers or consultants. As a PE firm, they’re trying to raise more money. They're always getting benchmarked by third parties and what they want, and those third parties want to see every detail at the PE firm level, as well as all the way down to the portfolio level.

And then they want to see consistency amongst the portfolio in terms of how they see the financials.

There are also people called placement agents. These guys are helping funds raise money, so they want to see financials all the way down.

You've also got investment bankers when you're selling or buying a company.

You've got tax/IRS, and you've got lenders (a lot of buyout firms use debt as part of their financing).

And then very last, I’ve put the actual company itself, the management team that needs the financials.

Oftentimes, the PE firms primarily care about their investors first, which is obviously not the right way to do it, but that's what they do.

So there are a lot of different constituents that they have to deal with in terms of financials, and what they want is consistency and clarity.

Sharing a financial reporting calendar with the CFO

When we buy a company, we typically buy control stakes, and often we're buying businesses where there's an owner who’s run their business for themselves for 20 years. Often, they may have a controller, they may have an AP person, and they may have a bookkeeper.

And then we come in and say, “We've got equity investors, we've got debt investors, and we've got reporting requirements.”

Then, we put together this nice, fancy corporate calendar and we tell them, “We need monthlies and we need quarterlies. We have compliance reports for the lenders, and we’ll have to do audits and budgets.” There's a whole bunch of stuff.

We try to put this in front of an owner, and usually, they get that look on their faces that says, What the hell is all this? Is this value add?

Of course it's not value add, but I have to do it anyway.

Often, what we see on the private equity side is that finance and marketing are two of the most under-invested departments of small businesses, and I don't blame them.

Often, a lot of businesses can just look at their cash flow and say, “Why do I have to do cash accrual accounting versus cash accounting? I just look at my bank balance every week. Cash goes up, I'm doing well. Cash goes down, I'm not doing well.”

We just bought a business that was 100 mil of revenue and doing 20 mil of cash flow a year. The owner just did it by looking at his bank statement every week. He didn't really have a full finance function. Cash flow was positive and he was doing great, but that's how he ran his business.

So we try to explain to them that when you take on institutional capital and you're taking liquidity out, part of your agreement is that you’ve now got to help the PE firm deal with all their constituents.

It's usually a challenge at first, but we figure it out and we work through it, and in almost every case, we end up either replacing or augmenting the company's financial controls.

It's not that they're doing a bad job, it's just that there's a different need now and there's a lot of constituents that we have to manage.

Key considerations for private equity firms

At the end of the day, what PE firms really want is to show up once a month and get their financial statements. When a firm starts digging in deeper, it’s because it's not doing well, or we're getting reports late, or it's inaccurate.

I was just reviewing the financials for a company this morning, and we found out that in January they moved some cogs around, and we're trying to figure out why they got moved around from the prior January.

So, when you think about what a PE firm really wants, they don't want to get involved. They just want to get their financial package monthly, they want to get their quarterly covenant statements for the banks, and then they want to get their audit at the end of the year.

The reason why we put all this emphasis upfront is because if you don't lay out this foundation upfront, you end up running into a problem.

Twice in my career, I've had to step in as an interim CFO when we couldn't get actual reporting. And I'm sitting next to the CEO, and he's telling me his bank balance is doing really well. But I'm saying, “Well, the marketing costs that you’ve put in here that you’ve spent $100,000 for this booth for the next 12 months, but you’ve put it all in the first month.” And I have to walk them through what a cash versus accrual is.

So, what we try to walk through is that every company is different with different KPIs, so we leave that to each company. We also want to understand the revenue cogs, gross profit, SG&A, and EBITDA.

The new common term in our world is ‘adjusted EBITDA,’ and if you don't know what that means, it's just whatever you can get away with with the lenders that makes the EBITDA higher. I’ve got to be honest, that's what we try to do.

And then, obviously, you want to understand the cash flow on the balance sheet, CapEx, networking capital, and taxes.

What's interesting is that PE firms want lots of data. Sometimes there's a lot of analysis for paralysis aspects in private equity. Firms will want to see year over year, month over month, year to date, actual versus budget, actual versus reforecast, and actual versus second reforecast. It can be mind-numbing.

We have a third-party firm that helps some of our smaller companies manage that. And then we're actually working with BSP and some other companies to help put in something adaptive that’ll help us do better planning.

The other big thing aside from monthly reporting is that there are K1s, audits lender compliance, and co-investor compliance.

The K1 thing is super critical for private equity firms. A lot of private equity firms will invest in a combination of flow-through and C corp. We no longer invest in flow-through entities. If a company is an LLC or an S corp, we’ll always put a blocker corp above it.

At my old firm, we ended up losing three investors because we couldn't get K1s at the time. The investor was livid that he had to do estimates and extensions.

The reason why a PE firm likes flow-through income is because they love taking that tax distribution and applying it to the IRR calculation for when they're fundraising. Now, you can make an argument that that’s really not kosher, but a lot of PE firms do that to juice up their IRR because they take those tax distributions through a flow-through.

Our view is to not play the IRR game and actually build businesses, so we put blocker corps in every one of our entities.

So, if there's an operating company, there's a blocker corp, and then we'll have an LLC where all the investors sit. And the point of that is, when investors get K1s, they say, “Hey, where's my K1?’ I can write back, ‘It's going to be zero. It may be late, but it'll be zero. You'll have no K1s.

And then the other issue that we ran into is, if a company’s selling in multiple states, that's a flow-through. You can file in 10, 20, or 30 states, and then you can allocate the income right across all those states. I remember that I had to file for Kentucky and Missouri for $1,000. So, it gets very mindful. Again, that's in the private equity world.

So K1s are super critical for private equity firms, getting them on time, and being accurate. Often, what happens is the PE firms don't appreciate how hard K1s are to get done properly. They'll shove it all down to the portfolio level.

So, if you're a CFO or a controller and you've been working for a privately owned family for a long time, and then you have a PE firm that shows up that took 20 investors in their fund, now you’ve got to generate K1s for 20 investors, plus the family across multiple states. It's often a, “What did I get myself into?” situation, and that's pretty important.

Also, in private equity, for most deals, you'll take on lenders and third-party debt, and they're going to require an audit. I've tried many times to get that to a review or compilation. I haven't succeeded once yet in getting that done. It's always been an audit, and audits are painful.

In a lot of these private companies, they’ve never had to do a full audit. There's a setup fee, it takes time, and often, lenders want the audit done 120 days after the year-end. We always try to push to get it to 270 days so we can get it done cheaper during the summertime. We try to play that game, but lenders often push back.

Again, when you're taking on capital from private equity, aside from the monthly reporting, you’ve got K1s and audits.

Navigating the nuances of lender reporting and compliance

Also with lenders, depending on what kind of money you've borrowed as part of the transaction, you've got compliance certificates as well as borrowing base certificates.

If you don't know what those are, some lenders will borrow against the assets of the company, and every quarter, you've got to show that you're compliant with that borrowing certificate. It could be based on AR, real estate, or inventory. What's the value of it? Are you in compliance?

And then often, if it's a cash flow lender, they have certain covenants. Fixed charge coverage ratio, which basically just means, what are your fixed expenses over your EBITDA? Or your total leverage, which is your total amount of debt divided by your earnings potential or your earnings.

If you haven't done those before, they can get pretty tricky.

When we do the leverage test, we try to use adjusted EBITDA and we try to get creative with that dynamic. I was going through one last week, where I told the controller, “Hey, let's add these four adjustments and see if we can get away with it with the lender. Let's just try and see what happens.”

My success rate is pretty high. If we're going to install an ERP implementation, there's probably $100,000 in implementation costs and then a monthly $5,000. I'm able to add $100,000 monthly. That's $100,000 one time, but not the $5,000 a month.

Or, if I hire a recruiter to hire a new head of sales, I can add the recruiting costs as a one-time expense.

You have to be reasonable in your requests. Where lenders push back or even we push back is if we see that same expense year over year over year, but then you should add it all back. That's where it gets tricky. But if it's truly one time, most lenders are pretty thoughtful.

Most lenders are also really busy. We have six companies and we're pretty busy. Enterprise is one of our lenders, and it's an eight-person team. I think there are 60 companies that they're managing, and they're getting compliance reports. So they just want it on time.

They're too busy to go and dig the weeds. They just want to get the reports to show to their credit underwriters that they're in good shape and move on.

When we're looking to sell a company, we walk through what we think is realistic. You can have a litmus test of what's going to pass and what's not.

You’ll often see in these small businesses that the owners try to increase their earnings by saying, “Hey, I don't need to be here anymore. You can go hire somebody.”

The biggest change we often see is, “Hey, I'm paying myself. I make $500,000 as CEO, but you really only need a CEO that's $200,000. That's usually the biggest change that we argue about with people and say that it’s not realistic.

The first time we show this to a controller or CFO and they’ve never done it before, it can be overwhelming for them. So we usually spend a fair amount of time making sure to ask, “Have you done compliance reporting? Have you dealt with the banks?”

Once you do it the first time, it's pretty easy the second time. The only time it gets tricky is if you end up failing a test, and that's when we have to deal with it separately. But if you've got a growing company, this should be pretty straightforward.

One of the things that we’ll share with the company and the finance department is the credit agreement, which is usually a 60 to 100-page document. We don't ask them to read it, but there are a lot of nuances in there of timing, the sample forms, and the definition of debt.

We just worked with a company the other day and they're pitching on some business up in New York to install new hardware for a school, but the school wanted a surety bond, which is another form of indebtedness. It’s a form of insurance policy.

Lenders will look at that type of insurance as additional debt, so lenders are going to have a restriction on how much more debt you can take on.

So, stuff like that we'll work through with the finance team to understand all those dynamics.

The last thing that we do is manage personal expenses. If you’re buying a private company that's owned by a family or an owner, they're shoving through a lot of their personal expenses to reduce their tax, which makes sense. Now you've got institutional investors.

One thing we forgot to do with one of the companies about seven years ago was we forgot to share. We agreed with the owner that he could no longer expense X, Y, and Z. The CFO didn't find out and we didn't pick up on it. So, for three years the owner kept expensing his personal cars and trips to Vegas.

Understanding what’s required, not required, what can be expensed, and what can’t be expensed through the company's P&L are important things to discuss with the finance team at the company.

But we usually try to come up with the templates, and then we walk the finance team through how to do it. It's not hard, it's just nerve-wracking the first time if you've never done it before.

Financial reporting challenges and best practices

We've learned a few best practices. One is people and understanding how strong the finance department is.

Early in my career, we probably looked at it as an oversight because we always focused on the growth drivers of the business. Now, we want to make sure that we always heavily invest in the finance department out of the gate, whether it's bringing a third-party accounting firm or a CFO firm to come in.

We'll sit down with the owner and ask, “Can the person or team you have today really do the FP&A and the controller function?” And if they can't, that's okay, let's either try to train them, or if they can't train them, then we’ll bring in an outside party. And so we spend a lot of time on that.

We also try to be very clear on communications in terms of what and when needs to be reported. At the end of the day, my job is to help strategically with the company on where to grow. I really don't want to be involved in the finances, except when we're dealing with the lender or the investors. So, we try to be very clear upfront, “Here's what we need, and here's what it should look like.”

So that's why we have that corporate calendar, which can be overwhelming, but we try to use that.

A lot of companies that we work with often start with QuickBooks, and we typically end up migrating them to NetSuite, Great Plains, or Sage.

We're actually going through two implementations now where we're going from QuickBooks to NetSuite and a third one. It's on Sage, but it’s looking to move to something else because it can't get the inventory reporting.

What we've learned is that one of the companies started an ERP implementation, but we put it on hold because they had no one at the company to actually manage it. So, we're going to hire a controller or senior finance person to manage that, and then we'll reengage on that.

So that's something that we spent a lot of time understanding: “What kind of accounting systems are you on?” And ensuring we had the right people to support that implementation.

We try to help get people packages of what we think they need to look like. Nothing is set in stone, but we try to get people what we think their monthly package should look like. Three statements, KPIs, MD&A.

And then the last piece is what we talked about, the K1s, audits, and tax estimates. Those are all critical parts of the reporting process from the company up to the PE firm.