In my former role as a consultant in the CFO Excellence practice at Boston Consulting Group, I had the opportunity (sometimes passively, often actively) to observe and shape Planning, Budgeting, and Forecasting (PBF) processes across industries including Consumer Goods, Financial Services, Pharmaceuticals, and Energy.

My initial impressions were twofold

The state is more fragile than many leaders realize

While it is expected that companies seeking external support have gaps, the baseline in some cases was startlingly low.

I encountered a Fortune 500 pharmaceutical company running completely disconnected processes for annual planning and capital projects.

At the extreme end, a large financial institution had no formal PBF process at all, enabled largely by the absence of external shareholders to hold management accountable.

Most organizations don’t have the toolkit to fix the issue

Even when CFOs clearly recognize these shortcomings, most organizations lack a practical toolkit to fix them. The intent to improve is often there; deployable frameworks and playbooks are not.

This article is my first attempt at addressing the second issue. In no way do I claim this is comprehensive or effective.

But this is a starting point and I am sure it will evolve as I think and write about it more, and more importantly, as I get feedback from this community.

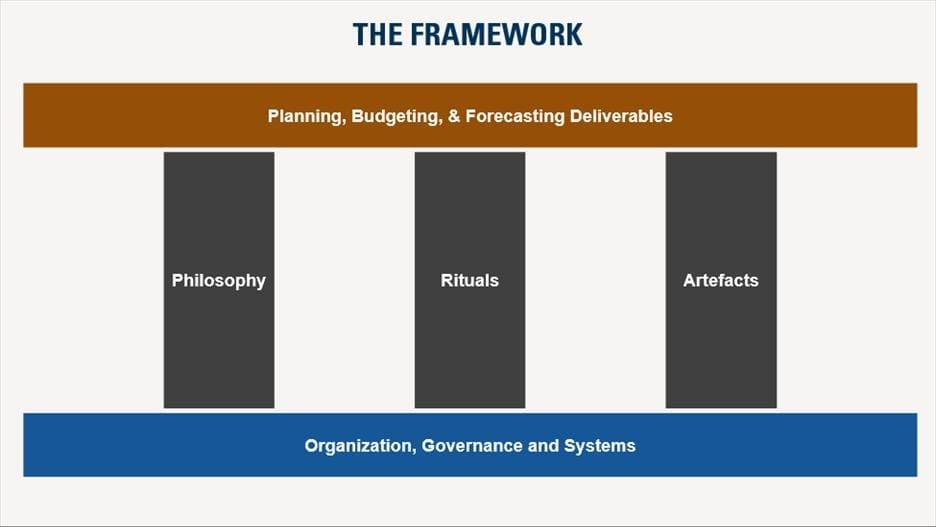

As any former consultant would, I have packaged this into an acronym: the F-PRA framework: Foundation, Philosophy, Rituals, and Artefacts.

It can be visualized as below:

Foundation: Getting the basics right

The foundation is the most critical element of the framework—and the one I will spend the least time on.

Not because it is unimportant, but because most organizations already have parts of it in place: defined organizational structures, ownership models, RACI matrices, and performance management systems.

A decade of wave of digital transformations has equipped most companies with reasonably mature KPI definitions and reporting tools.

However, having these components is not the same as having a foundation designed to support the desired PBF process.

If the organization structure and systems cannot support planning, forecasting, and—most importantly—execution, the rest of this framework is irrelevant.

One important caveat: as PBF processes evolve, the foundation must evolve with them.

Too often, organizations design PBF processes constrained by existing systems and structures, rather than allowing those foundations to adapt to the operating model they actually want.

The pillars: Process execution design

1. Philosophy

The first question that the CFO (typically in conjunction with the CEO) has to ask is what the PBF design principles are. There are many dimensions to this.

Control vs. autonomy

How much control should be exerted over the commercial teams to execute the plan? Do you want the process to be top-down (plans made based on goals given by leadership) or bottom-up (a roll up of individual goals) or somewhere in between?

A large European bank has institutionalized an ingenious process (and one of the best I have seen) where the PBF processes are driver based but has continuous forums that ensure that both management and field align on the drivers.

The finance team acts as a dispassionate party to deliver the numbers purely based on the drivers (very difficult to implement but highly effective if you can get it right).

Rigidity vs. flexibility

How frequently should forecasts be refreshed—annually, quarterly, monthly, or continuously?

How much latitude should teams have to adapt plans as conditions change? Equinor’s “Ambition to Action” framework represents one extreme: the traditional annual budget was eliminated in favor of continuous planning.

Each spend is treated as a project, resources are allocated dynamically, and returns drive decisions.

At the other end of the spectrum are organizations that lock budgets annually and require teams to justify predetermined top-down targets.

Role of PBF process

Is PBF primarily a tool for setting targets and enforcing accountability? Or is it intended to reflect economic reality as closely as possible and set expectations for shareholders?

Or both? The answer fundamentally shapes how the process is designed and used.

Ultimately, the key stakeholder to keep in mind is the shareholder. Risk tolerance, governance expectations, and desired involvement vary dramatically across ownership models—from founder-led private companies to PE-backed firms, state-owned enterprises, and widely held public companies.

When in doubt, the simplest advice applies: ask the board.

2. Rituals

Once you have the philosophy nailed down, the next step is to put in place rituals to bring the philosophy to life. The key design drivers within the rituals would be:

Objective of each ritual

Why do we have a ritual: is it to inform, discuss or decide? Or a combination of some or all of these? If it is to decide, which decisions and who will be the decision maker? How? Consensus or executive direction?

Active vs. passive

Would the ritual be a live forum for discussion or an offline update (email, dashboard etc.)?

An Indian industrial giant that I worked with to redesign their PBF process was very clear that they did not want any live governance forums between quarters.

All plan updates were done offline and business leaders could call their own individual meetings for decision making if required.

Frequency & triggers

How often should rituals occur? Should certain events trigger ad hoc sessions?

A downstream oil company tied reforecasting to petroleum price thresholds; when prices breached predefined ceilings or floors, a reforecast was triggered and discussed with the CFO, and new thresholds were set.

Stakeholders

Who will participate in which sessions? Who will get an update by when? Who can decide and whom do they consult with when they take a decision? Where are they located?

Fundamentally, the design of various rituals and their calendarization is driven by the first pillar: the PBF philosophy.

A rigid, top-down philosophy might engender a set of more frequent rituals, continuously updated dashboards, with heavier involvement by top management.

3. Artefacts

Rituals cannot function without relevant artefacts—presentations, dashboards, reports, or sometimes even just a number.

Artefacts are often treated as a tactical afterthought, but this underestimates their importance.

Artefacts are the primary interface between data and decision-making, and poorly designed artefacts can materially weaken even well-designed PBF philosophies and rituals.

Artefact design is driven by two factors: 1) The nature and objective of the ritual, and 2) What can realistically be measured and reported.

Designing effective artefacts is as much art as science and is influenced by leadership style, organizational culture, and decision maturity.

A useful lens for artefact design is the behavior they induce. Strong artefacts focus attention, surface trade-offs, and accelerate decisions.

Weak artefacts create noise, encourage gaming, and slow execution.

Some observed reasons for artefact design failures include:

- Signal dilution: Dashboards overloaded with KPIs dilute attention and shift discussions toward explaining numbers rather than making decisions.

- Narrative dominance: Excessive context and commentary obscure key trade-offs, turning decision forums into reporting sessions.

- False precision: Highly detailed forecasts presented with unwarranted certainty create a misleading sense of accuracy, particularly in volatile environments.

- Over-templatization: Excessive rigidity suppresses nuance and incentivizes teams to fit reality into predefined formats rather than surface emerging risks.

Strong artefact design, by contrast, typically exhibits a few consistent characteristics:

- Decision-oriented: Artefacts clearly indicate what decision is required and by whom.

- Focused: Emphasis is placed on a small number of critical drivers rather than exhaustive detail.

- Explicit about uncertainty: Ranges, scenarios, and sensitivities are often more informative than point estimates.

- Aligned to accountability: Ownership of assumptions and outputs is unambiguous.

One European financial institution I worked with enforced strict artefact standardization, trading flexibility for faster reviews, clearer escalation, and more disciplined governance.

In other organizations, particularly those emphasizing autonomy, lighter templates combined with strong narrative expectations proved more effective.

Ultimately, artefacts must be designed in service of the rituals they support and the philosophy they embody.

Treating artefact design as a low-value or cosmetic exercise overlooks its real role: shaping how leaders interpret reality and how effectively they act on it.

Conclusion

Sitting above the framework is its ultimate purpose: PBF outcomes (the roof in the framework).

Every element—foundation, philosophy, rituals, and artefacts—should serve the needs of stakeholders, particularly shareholders.

These outcomes may include earnings guidance, capital allocation decisions, pricing support, or broader strategic objectives.

Two closing thoughts bear repeating:

- The organizational and systems foundation should evolve based on the chosen PBF design, not constrain it.

- This framework represents an initial codification, not a finished product. I welcome feedback, perspectives, and challenges that can help refine and strengthen it over time.

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn