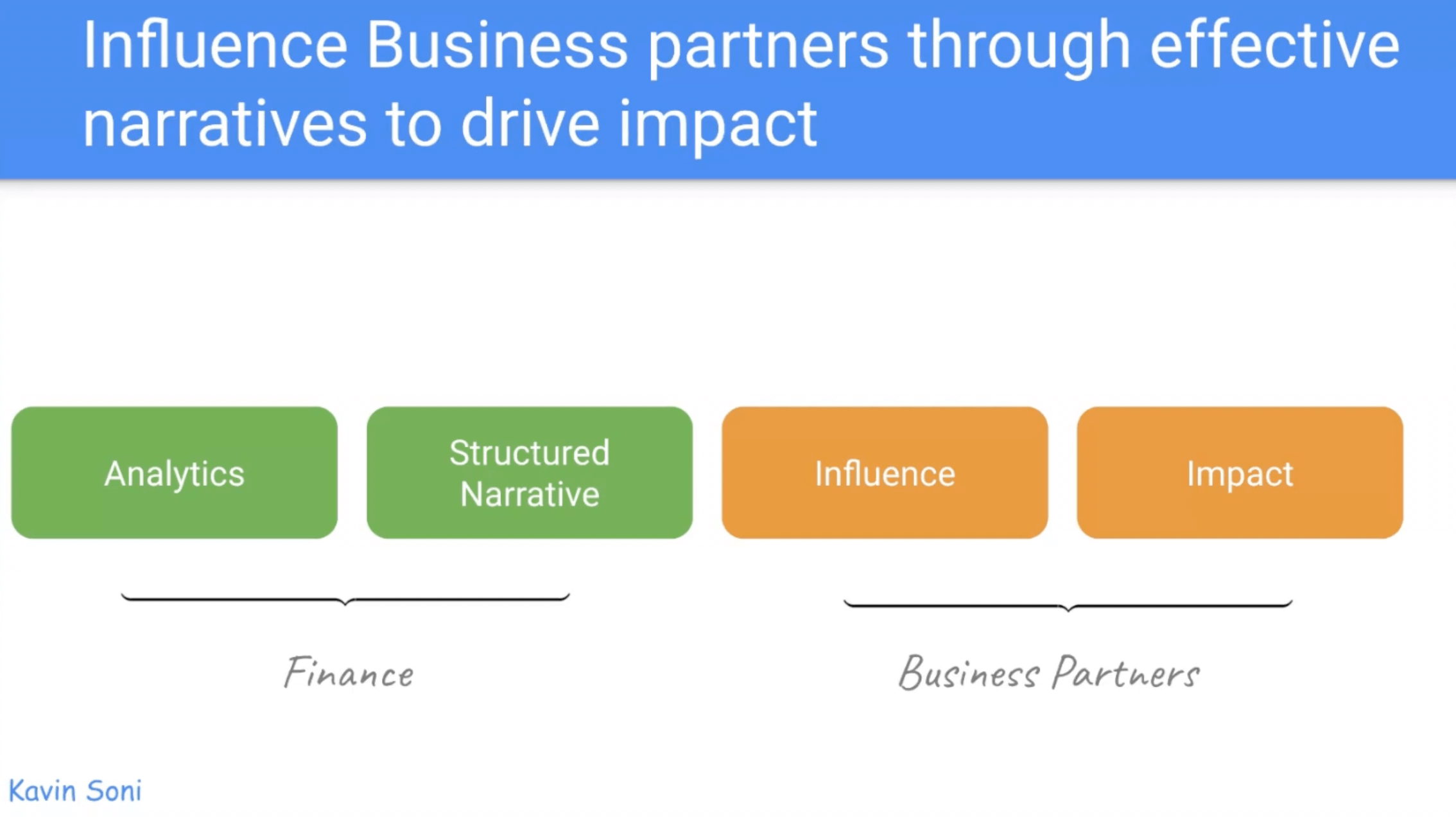

In finance (especially in FP&A) we don’t own a P&L line the way sales or product does. What we do own is perspective. We have the models, the benchmarks, the insights, and most importantly, the ability to bring structure to decisions.

But here’s the catch: insight alone doesn’t drive outcomes. To have impact, we need to shape a narrative that resonates with our partners and use that narrative to influence. That’s how finance becomes more than the “number crunchers” in the room, we become trusted advisors and decision-makers.

In this blog, I’ll share a framework I’ve developed for doing just that: moving from analytics, to narrative, to influence. I’ll also cover some of the pitfalls I see new analysts fall into, and how to avoid them.

Why you need to tailor your narrative

The starting point for any narrative is knowing your audience. Too often we focus on what we want to say, not what our audience needs to hear.

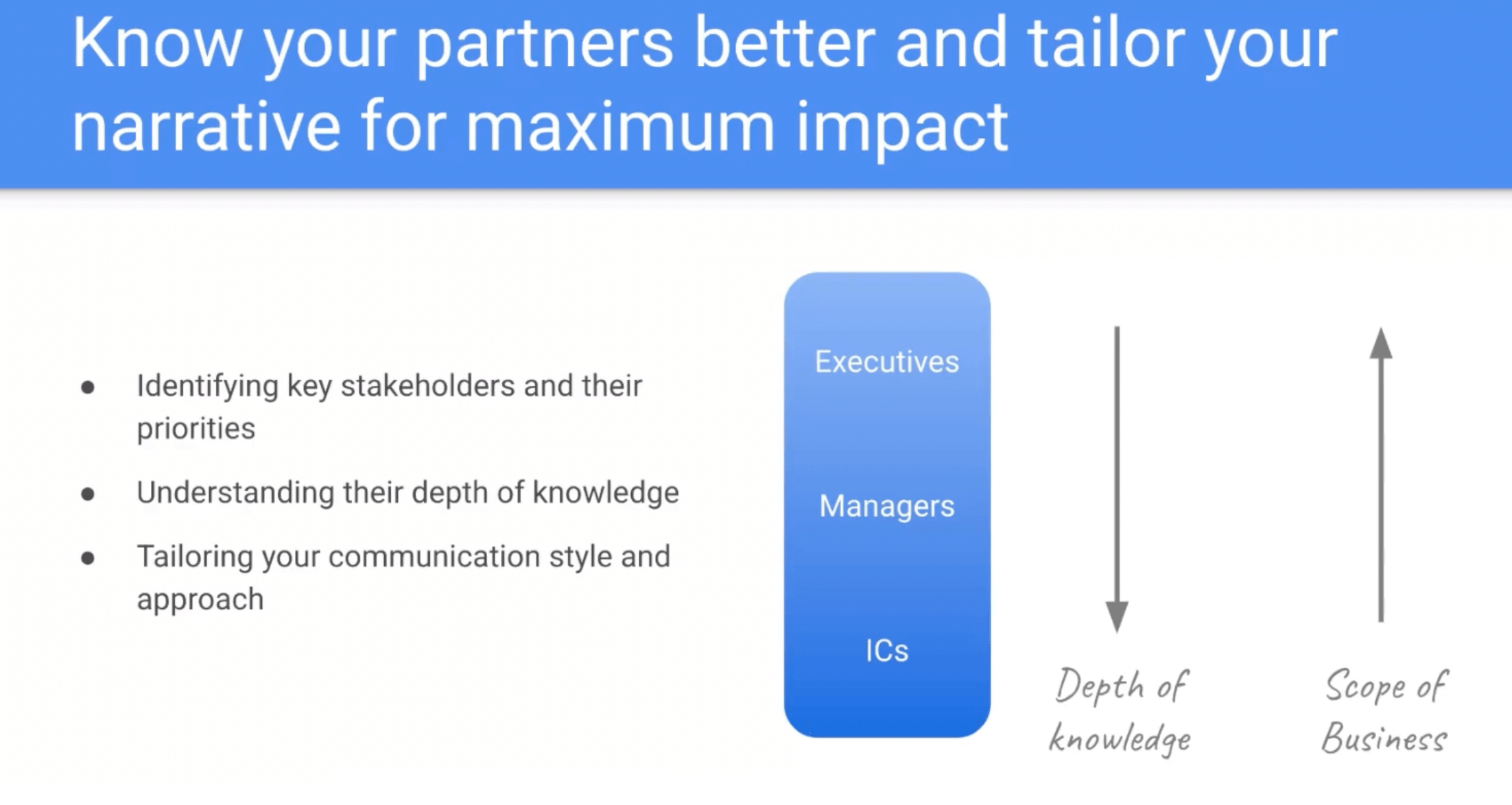

Every stakeholder comes with two defining traits: their priorities and their depth of knowledge.

- Executives: broad scope, but shallow detail. They want the headline, the “so what,” and they want it fast.

- Managers: balance of depth and scope. They need enough detail to understand drivers but don’t want to drown in data.

- Analysts/ICs: deep experts in their corner of the business. They want to see the data, the methodology, and the steps you took.

If you give executives 20 data slides, you’ll lose them. If you give an analyst just a headline, they’ll dismiss you. The art is tailoring your narrative to the level of your audience.

The hypothesis-driven analysis approach

One mistake I see often (especially with new analysts) is diving straight into the dataset the moment they hear about a problem. They start pulling numbers, running pivots, and building models without stopping to frame the story first.

The problem with this approach is twofold:

- You overwhelm yourself. Datasets are messy and sprawling. Without a clear hypothesis, it’s easy to get lost in noise and lose sight of the real issue.

- Storytelling becomes harder. If you start with raw data, you end up trying to stitch together a narrative after the fact. That often leads to a fragmented or overly technical presentation that doesn’t resonate with stakeholders.

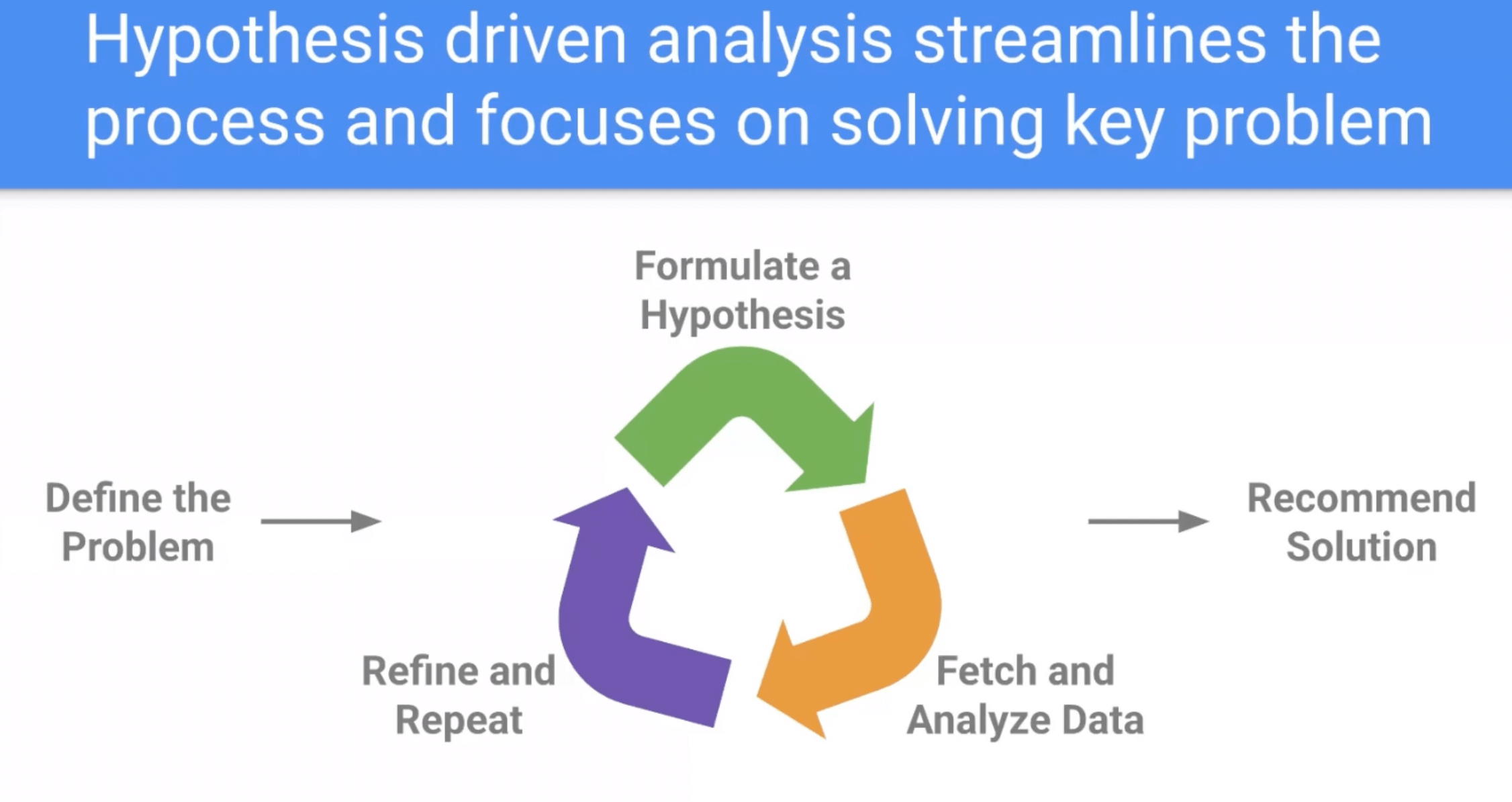

A hypothesis-driven approach flips this. Start by asking: What’s the problem? What do we think might be driving it?

Then fetch and analyze the data to confirm or refine. This way, the data fills in the story you’ve already sketched, instead of leaving you scrambling to invent one afterward.

The better way to approach this is with hypothesis-driven framework:

- Define the problem.

- Form a hypothesis about the cause.

- Collect and analyze data to test that hypothesis.

- Refine and repeat until the story is clear.

Starting with a hypothesis prevents overwhelm, keeps you focused on solving the actual problem, and makes it much easier to connect the dots in your storytelling.

Transforming data into actionable insights

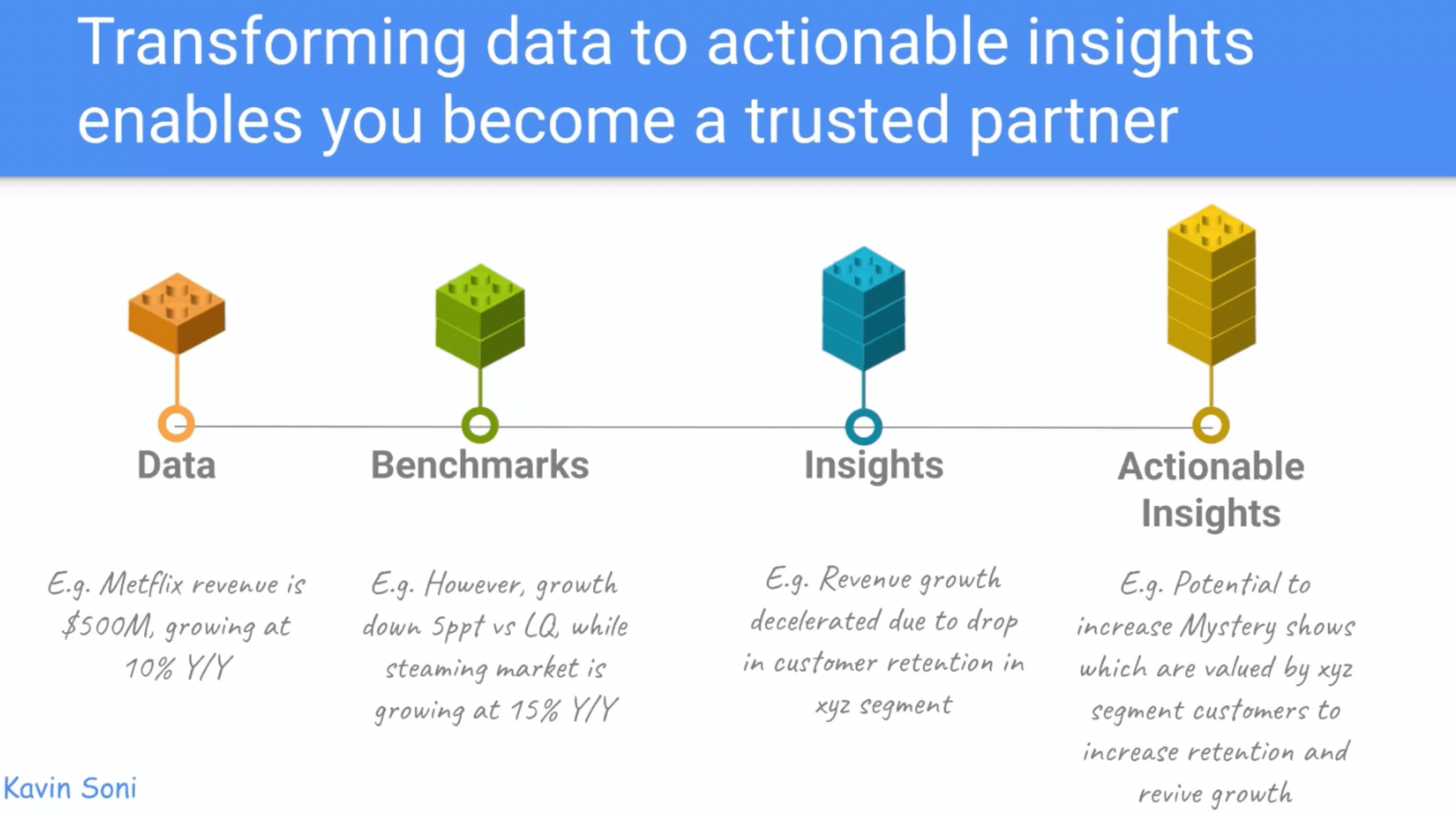

Data is only the starting point. It’s not about what the numbers say; it’s about what they mean.

Take a Netflix example:

- Data: Revenue is $500M, up 10%. Not bad, but not meaningful on its own.

- Benchmark: Growth is five points below market and slipping versus last quarter. Now it’s a problem.

- Insight: Digging deeper, you find retention is dropping in one key segment. Suddenly we know what’s driving the slowdown.

- Recommendation: That segment values thrillers and mystery shows. Investing more there could boost retention and revive growth.

That last step (the recommendation) is what separates “data providers” from trusted partners.

If your work stops at metrics, you’re a report generator. If you connect metrics to business drivers and actions, you’re a decision-maker.

One trick I use is the “five-year-old test”: could I explain my insight in simple enough terms that a child would get it? If not, I need to simplify further. The extra detail can always be held back for Q&A.

Identify your stakeholders

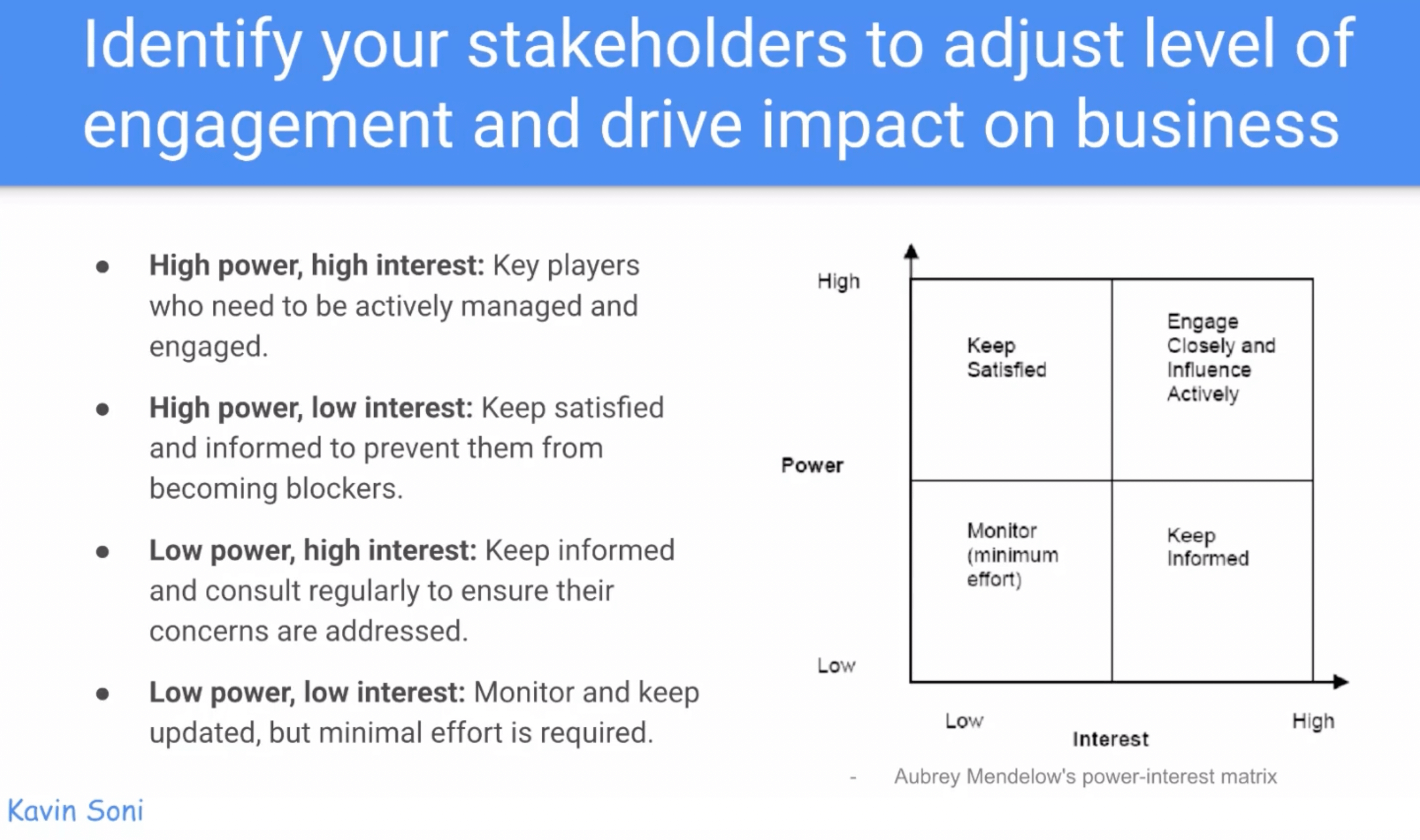

Even the best story won’t matter if it’s told to the wrong people. That’s where stakeholder mapping comes in.

The classic power vs. interest framework is a great guide:

- High power, high interest: Your key players. These are the partners you must engage deeply.

- High power, low interest: Keep them satisfied so they don’t become blockers.

- Low power, high interest: Keep them involved, but don’t overinvest.

- Low power, low interest: Monitor lightly.

In my role at Google, product managers and GTM strategy leaders are top-right stakeholders. They’re the ones whose buy-in determines whether analysis turns into action.

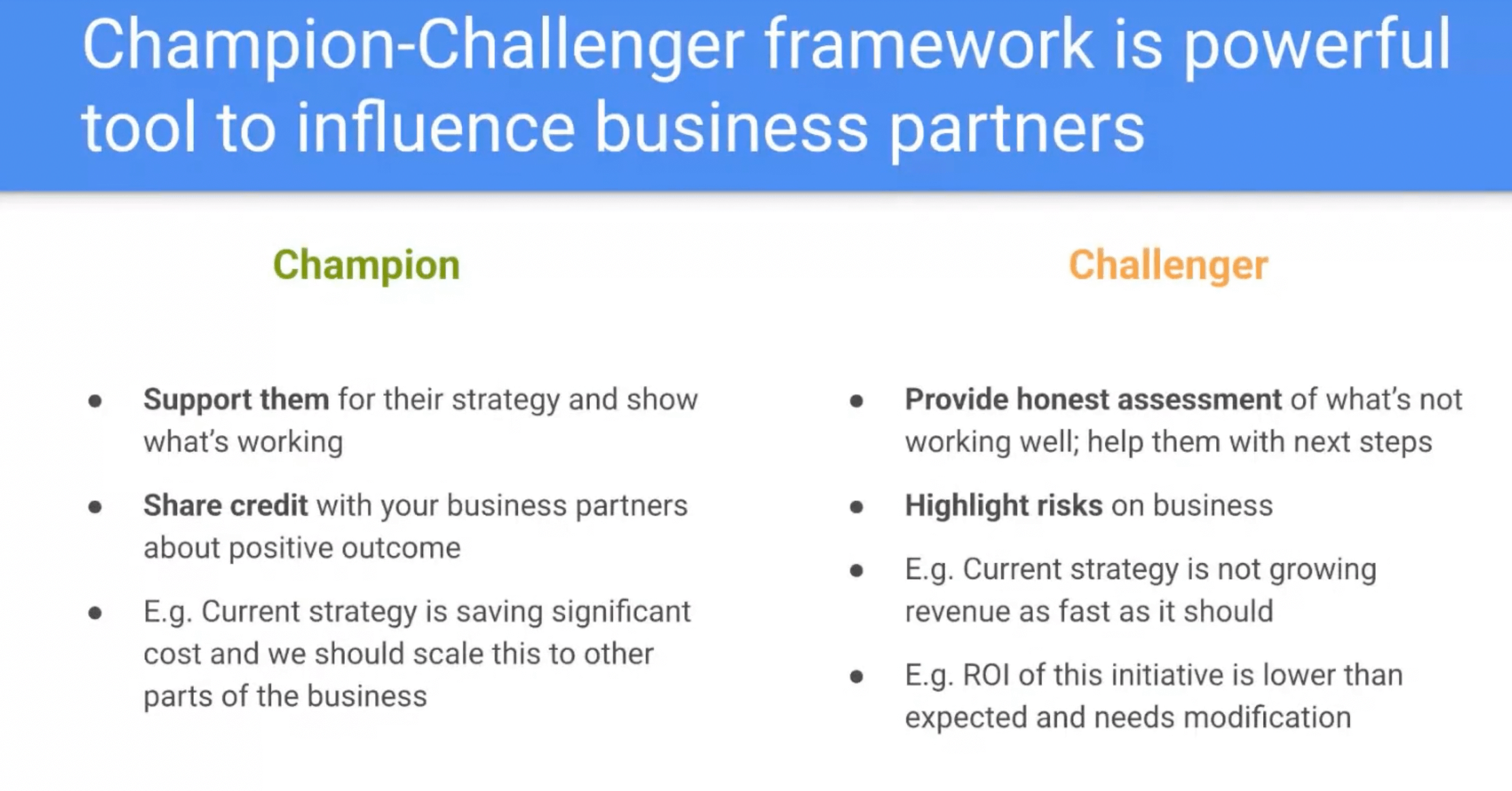

The dual role: Champion and challenger

Finance plays its role most powerfully when we balance two modes: champion and challenger.

- Champion: This is where you recognize what’s working and amplify it. Celebrate wins with your partners, share credit generously, and show how their strategy can scale even further. For example, if a product team’s campaign is hitting its ROI targets, we in finance can demonstrate how those tactics could extend into other regions or business lines. This builds goodwill and positions us as allies.

- Challenger: The harder role (but equally vital) is being the objective voice when things aren’t working. Say revenue is decelerating or the ROI on a new initiative doesn’t justify the spend. It’s our job to bring that to the table, backed with data, and propose better options. During business planning, that might mean questioning why resources are going to lower-ROI projects when stronger ones are being underfunded.

The key is balance. If finance only ever champions, we become cheerleaders. If we only ever challenge, we become blockers. But when we do both, we earn trust and respect.

Influence business partners through effective narratives

The challenger role requires tact. Here are the three pillars I use:

- Ask probing questions. Instead of bluntly saying “this won’t work,” challenge assumptions. Try: “What assumptions are we making here? What happens if retention doesn’t improve?” or “Have we thought through potential weaknesses?” This reframes critique as curiosity.

- Offer alternative solutions. Never point out a flaw without suggesting a better path. For example: “I see ROI is slipping in this initiative—what if we shifted spend to this other campaign where results are stronger?” That way, you’re enabling, not obstructing.

- Use collaborative language. Words matter. Replace “you’re wrong” with “I have a different perspective.” Swap “this won’t work” for “let’s try another approach.” Phrasing challenges as opportunities creates a sense of shared ownership rather than confrontation.

These techniques help finance maintain credibility as an honest broker while still preserving relationships.

Tailoring to different departments

It’s also important to recognize that different departments come with different cultures and priorities:

Legal tends to be defensive and risk-averse. When partnering with them, you need to come prepared with thorough due diligence and airtight reasoning, because they’ll scrutinize everything.

Sales, on the other hand, is fast-moving and action-oriented. They often prioritize speed over detail. When working with sales, trim the caveats, keep the message tight, and focus on the upside potential.

Understanding these differences helps you adapt your style. Cross-functional collaboration isn’t about forcing everyone to work the way finance does, it’s about meeting partners where they are, while still holding the line on sound decision-making.

This article is based on Kavin Soni's brilliant talk at the CFO Summit. Finance Alliance members can enjoy the complete recording here.

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn